Fixed Mobile Convergence Is Back, Baby

How Telcos Are Rebuilding Convergence as an Operating Model to Control Households, Cut Churn, and Shift the Economics of Connectivity

FMC Reboots: From Failed Promise to Strategic Necessity

Fixed Mobile Convergence was supposed to be the big unlock a decade ago. One bill, one box, one operator for everything: mobile, broadband, TV, Wi-Fi. It looked clean on paper: quad-play bundles, shared devices, and seamless handoffs from mobile to home Wi-Fi. But it didn’t work. The networks weren’t ready. OSS and billing systems couldn’t talk to each other. Routers were dumb. The phone might drop your call the moment you step out the front door. And the commercial pitch? Mostly discounts. Operators traded ARPU for volume and still experienced churn. By 2015, FMC had disappeared from most boardroom decks.

That’s changed.

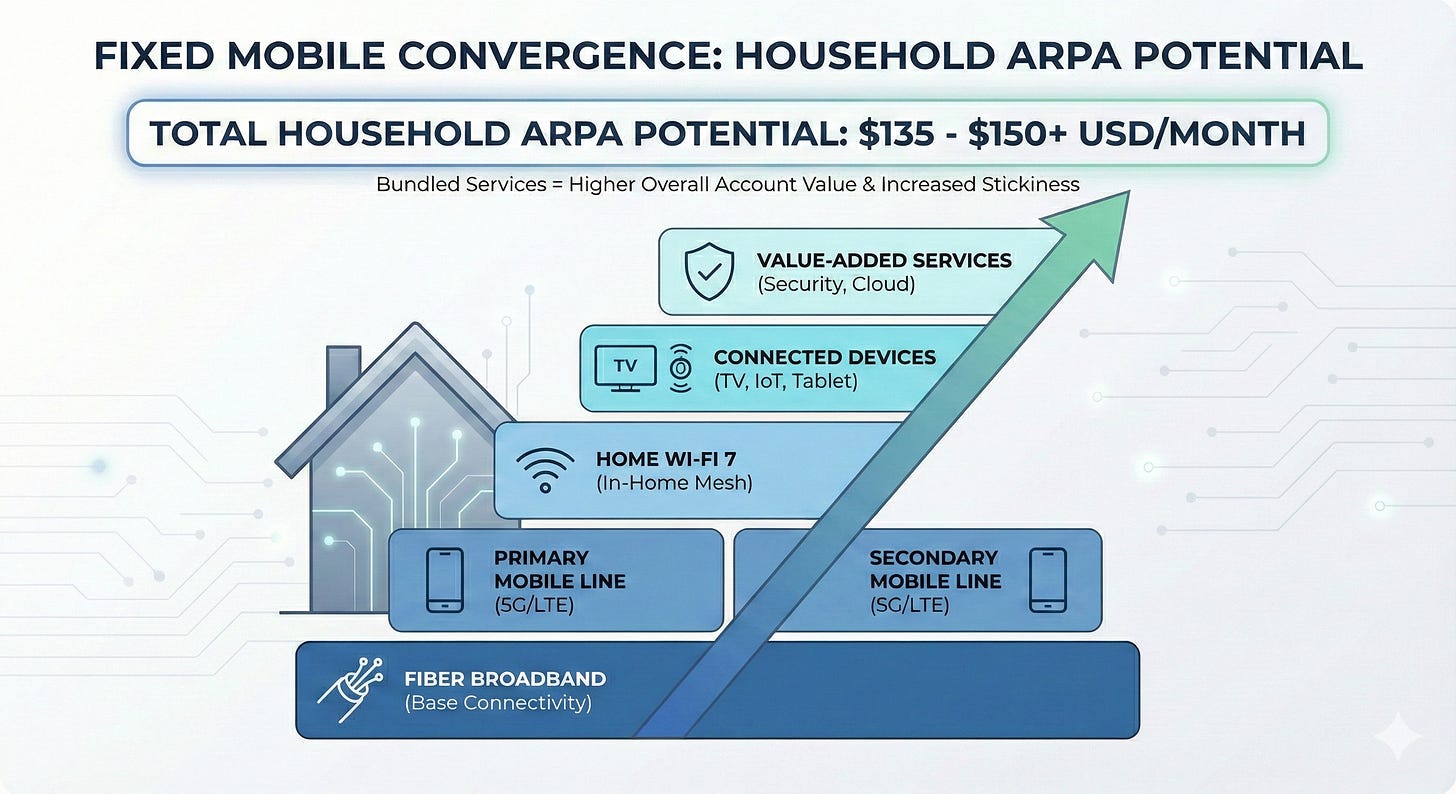

In 2026, FMC is back, and this time it’s not about packaging but all about ambient connectivity, churn reduction, escaping saturation, and focus on ARPA.

Mobile growth is flat. Everyone already has a phone. What carriers want now is to own the household. If you take the U.S. as a clear example, there are 130 million broadband-connected homes, each with three to five mobile devices, TVs, speakers, tablets, and laptops. Whoever controls the fixed line controls the entire digital stack inside the house.

So it’s not bundle-only anymore, but a platform war.

Verizon made the biggest move. It spent $20 billion to buy Frontier Communications, doubling its fiber footprint to 30 million homes. The goal is convergence. A household on Verizon fiber and mobile is twice as sticky. Internal churn drops by 50% on mobile, 40% on fixed. That translates into lower SAC, higher LTV, and fewer promo cycles. The company expects $500 million in annual operational synergies from integration alone by 2029.